It is normal for young children to display speech-sound errors that they will outgrow as they get older. A hallmark feature of many young children’s speech is substituting “W” for “R”. This error may make it sound like a child is saying “Little Wed Widing Hood” for “Little Red Riding Hood.” While this pattern is common for toddlers and preschoolers, children are expected to produce /r/ correctly by the early elementary years. Since /r/ is one of the most common sounds in the English language, it is no surprise that children who display difficulty with this sound will be difficult to understand. Most of us can speak clearly and precisely without thinking twice, so we may take for granted the intricacy and complexity involved in accurately producing speech. When speaking, a child must coordinate precise movements of the lips, tongue, and jaw along with their breath and voicing. All of this allows them to arrive at specific sound targets, seamlessly flowing from one sound to another to create meaningful words and sentences. If any part of the specific pattern required to produce a sound is just the tiniest bit off, it will result in an articulation error. Speech-language pathologists use many methods to teach children to coordinate the various aspects of the speech system to incorporate new sounds into their speech. Once the child is able to produce a sound in isolation, the speech-language pathologist supports him or her to use the sound in words, sentences, and finally in conversation. It is not an easy task to learn a new sound when you have never produced it before! /r/ in particular is a hard sound to teach even in isolation for many reasons. Below are the three top reasons why so many kids have trouble producing the /r/ sound.

1. Abstract motor movements

Unlike many other speech-sounds, the motor patterns involved in /r/ are not easy to see. Take for instance, bilabial sounds (in other words, sounds that require the lips to come together). A child can easily see that the lips must be closed to produce the /b/, /p/, and /m/ sounds, making those sounds easier to teach and learn. Additionally, for sounds like /t/, /d/, and /n/, a child can see that the tongue should be placed on the ridge just behind the top front teeth (alveolar ridge) to produce this sound. While most kids (and adults!) will not be able to tell you where they are placing their tongue to produce a given sound, being able to visualize the position of the articulators (lips, tongue, and jaw) is helpful for learning. It is very difficult to see where the tongue should be held inside the mouth to create a good “R” sound.

2. Different ways to make the /r/ sound

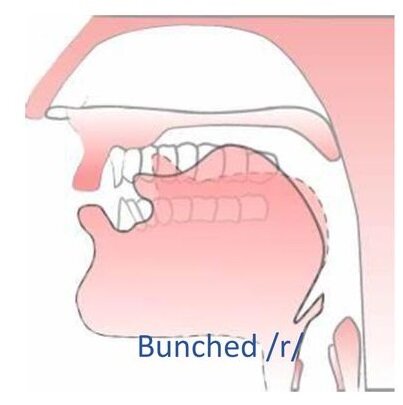

So how should the lips, tongue, and jaw be positioned to create a good /r/ sound? There are a few different configurations that can be used, and different people may interchange the positions in different contexts (Westbury, Hashi & Lindstrom, 1998). A few criteria, however, must be met for the /r/ sound to be produced: The tongue is held in the middle of the mouth, the tongue creates a ridge or hump to constrict airflow through the oral cavity, and the sides of the tongue make contact or approximate contact with the inside portion of the back molars. Below are the two major configurations that are produced when making the /r/ sound: , Bunched “R”: In this configuration, the tongue is “scrunched” tightly towards the middle/back of the oral cavity with the tongue tip down. The central portion of the tongue makes a hump that gently touches the hard palate. Retroflexed “R”: The configuration is produced with the tongue tip facing upwards, almost touching the palate.

3. Not just one “R” sound

The letter “R” is actually associated with many different speech sounds! “R” sometimes acts like a consonant. “R” usually acts like a consonant when it comes before a vowel, such as in “red,” “around,” and “green.” “R” can also act like a vowel. R acts like a vowel in words such as “feather,” “learn,” and “fur.” Children may be able to produce “R” in some contexts, but not others. To make matters more complicated, there are many variations of the vocalic “R” that all require slightly different transitions from the preceding sound to the /r/ sound. These vocalic variations include “AR,” “EAR,” “ER” “IRE” and “OR.” These vowels all require slightly different transitions from one articulatory gesture to another, and just because a child is able to produce one variation does not mean they can automatically produce the rest. For example, a child may be able to accurately produce words with “AR,” such as “star” or “army,” but struggle to use words with “OR” such as “more” or “boring.” The good news is, targeted practice with one variation of “R” often results in generalization to at least some untrained versions (Hoffman, 1983). Still, children with “R” difficulties typically need practice with several different variations of the sound in different word positions before mastering “R” in all contexts.

As you can imagine, the “R” sound takes time and patience to learn, as it is very complex. If your child is not consistently producing the “R” sound by the time they are in first or second grade, it may be time to consult with a certified speech-language pathologist.

References:

Hoffman, P. R. (1983). Interallophonic Generalization of /r/ Training. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 48(2), 215–221. doi: 10.1044/jshd.4802.215

Westbury, J. R., Hashi, M., & Lindstrom, M. J. (1998). Differences among speakers in lingual articulation for American English /ɹ/. Speech Communication, 26(3), 203–226. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6393(98)00058-2